יול 01 2012

שרצים – מאת: כרמלה וייס

קווי תפר חברתיים, רוע, חרדת המוות וגעגועים לאלה שאינם, נבחנים בתערוכה זו דרך העיסוק בשרצים למיניהם, ובכללם חסרי חוליות, יונקים קטנים, זוחלים ודו-חיים, פרוקי רגליים, תולעים ורכיכות.

אין מדובר רק בשרץ המוגדר בהלכה היהודית, בהלכות טומאה וטהרה, אלא בהרחבת היריעה תוך מרידה בנהוג ובנכון, ותוך קריצה לעבר הדבר שאינו במקומו וערעור על הסדר "הנכון".

רבי יהודה הלוי, כותב בספר הכוזרי, שהיסוד המשותף לכל מיני הטומאות הוא המוות: "שאפשר שתהיה הצרעת והזיבות תלויות בטומאת המת, כי המוות הוא ההפסד הגדול" [1]

על אותה הדרך, מרי דגלס, אשר חקרה את בני ה'ללה' מקונגו אומרת: "ה'ללה' הניחו שלאחר המוות, המתים מפתחים יחסי ידידות עם חיות מתחפרות ששכנו באותה ממלכה." [2]

אסי משולם ממקד ואומר: ""תולעה", במסגרת פולחן-הטומאה, הוא כינוי כולל לתולעים, לרימות ולזחלים הבאים אל בשר הנבלה וניזונים ממנו ה"תולעה", למעשה, מהווה בתורתו של "רועכם" כעין מונח מקביל ונרדף למונח "מוות", והיא מייצגת את התפיסה כי כל היצורים החיים הנם בני-מוות, וגופם הוא בשר שסופו להירקב ולהיאכל בידי אחרים ]…[ התולעה היא סמל לחיים הניזונים מן המוות ומשגשגים באמצעותו"[3] החיים עצמם נבנים מתוך המוות והריקבון.

כל השלושה מזהים, איפוא, את המוות בשרצים.

כמו הגרוטסקה, עליה כותבת ד"ר אלדובי חוה ה"משמשת כאמצעי הגנה מפני האימה שמעורר העולם שאותו היא מייצגת"[4] , כך הייצוג האמנותי של השרצים והעיסוק בהם הנו חתרני ומאפשר לגעת בחטא, בדוחה, במאיים, בנחות, באסור, בנסתר, באחר, במפלצת, באפלה. עצם ייצוגו האמנותי של הממד האפל מספק הקלה בחרדה, משום שהוא מאפשר מפגש עם אותו ממד, והכרות עם הייצוג של המוות.

כמו הגרוטסקה ה"מגלמת ניסיון להעלות באוב את האספקטים הדמוניים של העולם כדי לביית אותם, מתוך הבנה כי לא ניתן להכניעם."[5] כך הקרבה לתולעים והשרצים, שניזונים מהחומר ממנו עשויים אנו, מפחיתה את האימה ומנכסת את המוות.

האמן נוגע בחטא ומתיידד עם המוות.

אסי משולם מציג את האופנים בהם החיים עצמם מתפתחים ומשגשגים מתוך הריקבון והמוות. "התולעה והזבובה", מושג מכונן בתפיסתו של מסדר הטומאה שייסד משולם, מציע את עצמו כחלופה לתפיסות "החיים-שלאחר-המוות" כפי שהן מופיעות בדתות השונות (גלגול נשמות, גן עדן וגיהנום, חזרה מן המתים וכדומה). כס העלוקות, אם כך, מייצג את מילויו של ההיעדר – את החיים המושרצים מן האין.

יעל מרגלית עוסקת במפגש בין חומר ורוח, היווצרות והיעלמות, יש ואין.היא יוצרת דמויות מתהוות – נמוגות, פני שטח מעל ומתחת לאדמה. מרגלית משתמשת בצמר כבשים טבעי ובדיו, בתהליך הטבילה מתקבלים אובייקטים כתמיים, המזכירים גלמים או עדויות של חומר בעל עורקים או ורידים.היצור אינו מוגדר, ויכול להפוך לכל דבר. בעבודה "משא ומתן" מונחת הזיקית ככתם בזמן על טקסט שגם הוא יכול להיתפס כאוסף של כתמי דיו. השרץ מופיע כמהות קדומה, כשלב בתהליך ההתפתחות שבין רוח לחומר.

כרמלה וייס מונעת מגעגועים לאלה שאינם. תחושת הידידות עם המוות מצמצמת לכאורה את המרחק שנוצר ברגע ההעלמות. בתערוכה 'עיר סמויה' חיפשה כרמלה וייס את השרצים מתחת לאדמה ובקירות. היום הם נמצאים על פני השטח ומקבלים במה נאותה.

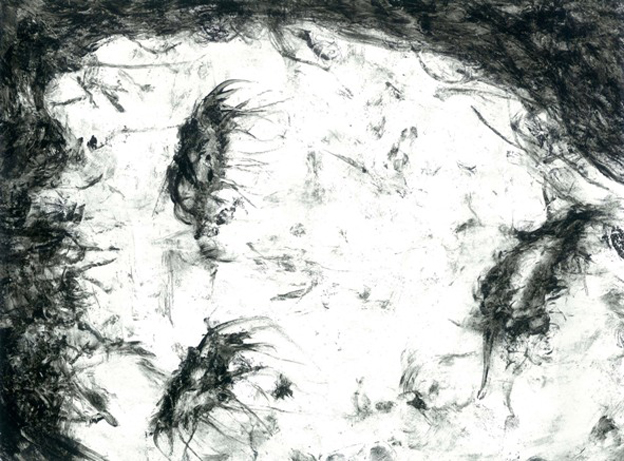

שחר קורנבליט מתמודד עם חרדת המוות בכלל ושל האם בפרט על ידי הבאת רגע של אסון אל מול עינו של הצופה, רגע שבדרך כלל נמנעים מלהביט בו או להתמודד עימו, ואפילו מעמיק אל דימוי של הרגע שאחרי. אלמנטים שונים למשל היות הדיוקן מקוטע, נטול צבע ושוכב/אופקי, מהווים חלק מהאמצעים הצורניים המבטאים את ההישארות הדוממת של אדם ללא רוח חיים פיסה של אמת במערומיה.

תומר ספיר קורא תיגר על חלוקות דיכוטומיות רווחות דוגמת טוב ורע, זכר ונקבה, חיים ומוות ובוחן קווי תפר תרבותיים. יצירי הכלאיים שלו מגלמים בתוכם מעין מוּטציה שמרכיביה נעים בין האורגני למלאכותי, בין הפתייני למאיים.ספיר מלקט אובייקטים מסוגים שונים המשולבים בעבודות הפיסול שלו, תוך שיבוש הטבע והיתוך בין עולמות החי והדומם ובין הממשי והבדוי.עבודתו מקובעת באזור הדמדומים שבין הטבעי למלאכותי, בתחום המחיה שבו שוכנים יצורים מיתולוגיים מדומיינים ומשובטים.

[1] רבי יהודה הלוי ,ספר הכוזרי , מאמר שני ,טומאה ,ס.

[2] מרי דגלס 'טוהר וסכנה' ניתוח של המושגים זיהוי וטאבו הוצאת רסלינג ע. 9

[3] אסי משולם מניפסט מסדר הטומאה, לקסיקון העיקרים,כרך ת

[4] ד"ר אלדובי חוה משקפים 40 : כיעור עמוד 6-11 מרץ 2000

[5] ד"ר אלדובי חוה משקפים 40 : כיעור עמוד 6-11 מרץ 2000

—

Social fault-lines, evil and the longing for those who are gone are explored in this exhibition through the preoccupation with various vermin, such as invertebrate, small mammals, reptilians and amphibians, arthropods, worms and molluscs.

It is not with regard solely to the vermin as it is defined in the Jewish traditional Halakha in the rulings relating to purity and impurity, but about extending the platform while rebelling against the customary and correct, as while winking at the thing that is out of place and undermining the “right” order.

Rabbi Yehuda ha-Levi, author of the The Kuzari, suggested that the common ground to all impurities is death: as the leprosy and menstruation are dependent upon the impurity of the dead, for death is a great loss.[1]

Similarly, Mary Douglas, who has researched the Lele claims that the Lele assumed that after death the dead develop a friendly relationship with animals that dig into the same kingdom.[2]

Assi Meshullam refines and says ”worm”, within the impurity ritual is a general term for worms, larvae and caterpillars that feed upon the flesh of the corpse. The “worm”, in fact, functions in the teaching of “thy shepherd” as a substitute and auxiliary term for “death”, and it is represents the perception that all living creatures are mortal, and their bodies is flesh predestined to rot and be eaten by others […] the worm is a symbol for life feeding off death and flourishing through it.[3] Life itself is built from death and decay.

All three, hence, recognize death in vermin.

Like the grotesque, of which Eve Eldubi writes, functions as a means of protection against the horror the world evokes it represents.[4] Thus, the artistic representation of, and preoccupation with vermin is subversive, and allows us to touch sin, the repulsive, threatening, inferior, forbidden, hidden, other, monstrous, darkness. The very artistic representation of the dark side provides relief of the anxiety, because it allows an encounter with that dimension and the representation of death.

Similarly to the grotesque that embodies an attempt to conjure up the demonic aspects of the world in order to domesticate them, from an understanding that they cannot be defeated,[5] so the proximity to the worm and vermin that feed upon the material of which we are made, diminishes the horror and appropriates death.

The artist touches sin and befriends death.

Assi Meshullam presents the manners by which life is built from within death and rot. Alongside the violence and death, Meshullam presents life growing precisely from the very same death and violence, as they are expressed in larvae and fly. The violence, destruction, death, lack of order and filth – all become therefore life itself for Meshullam.

Yael Margalit deals with the encounter between matter and spirit, creation and disappearance, existence and nullity. She creates immerging–fading figures, surfaces above and below the ground. Margalit uses natural sheep wool and ink, and in the dipping process blotchy objects appear, reminiscent of cocoons or evidence of matter with veins or arteries. The creature is not defined, and can transform into anything. In “Negotiation” the chameleon is laid as a blemish in time upon a text which can also be perceived as a collection of ink marks. The vermin appears as a primal existence, and evolutionary stage between matter and spirit.

Carmela Weiss is driven by longing to those who are gone. The friendly feeling with death appears to diminish the distance created at the moment of disappearance. In “HiddenCity” Weiss sought the vermin under the ground and in the walls; today they exist on the surface receiving an adequate stage.

Shahar Kornblit deals with the general as well as maternal death-anxiety by capturing a moment of devastation in front of the viewer’ eyes, a moment that one usually looks away from, or refrains from confronting, and even deepens towards an image of the following moment. Various elements such as the fragmentation of the portrait, its lack of color and horizontal design are a part of the formalistic devices that express the silent remaining of a person without the breath of life, a piece of naked truth.

Tomer Sapir challenges the prevalent dichotomous division such as good and evil, male and female, life and death, and examines cultural fault-lines. His hybrid creatures embody akind of mutation whose components meander between the organic and artificial, the seductive and threatening. Sapir collects various kinds of object that are incorporated in his sculptures, while disturbing nature and fusing the worlds of the animate and inanimate, the real and fictional. His work is fixated in the twilight zone between the natural and artificial, in the habitat in which mythological, imagined, and cloned creatures dwell.

[1] Ha-Levi, Rabbi Yehuda. The Kuzari. Second Essay; Impurity: 60.

[2] Douglas, Mary. Purity and Danger: An Analysis of Concepts of Pollution and Taboo.London : Routledge & K. Paul, 1966.

[3] Meshullam, Assi. Manifesto of the Order of Impurity: The Principle Lexicon. Vol. 200.

[4] Eldubi, Eve. ‘Kiur Amud’. Mishkafayim: 40, March 2000; 6-11.

[5] Ibid.

—

מתוך התערוכה:

—-

גלריה P8, רח' פוריה 8, יפו.

מציגים: אסי משולם, יעל מרגלית, כרמלה וייס, שחר קורנבליט, תומר ספיר.

אוצרת: כרמלה וייס.

נעילה: 28.7.2012

תגובה אחת לפוסט “שרצים – מאת: כרמלה וייס”

זה לא אני, זה המצב!

Copyright © 2026 כל הזכויות שמורות .

זה לא אני, זה המצב!

Copyright © 2026 כל הזכויות שמורות .

הטיפול בשרצים למינהם ממש מרתק,

תודה לך דורית על הדברים שהעלית כאן